Uterish Book Club Picks of the Year 2022

Did you tune in every month and read our Uterish Book Club Picks on The Provocateur? Is this the first you are hearing of it? Welcome to our full round-up of each book we selected and wrote about on The Provocateur, our monthly newsletter, in 2022!

JANUARY

Greta’s Pick —

Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts is a work of its own genre––commingling memoir, theory, art criticism, and personal nonfiction while for some reason living in the “essay” section at Elliot Bay Bookstore––that is nearly impossible to describe. But I am going to try anyway! Because if there is one book I could recommend to everyone, it would be The Argonauts. In it, Maggie Nelson explores queerness, love, community-building, and gender through the lens of her own life. The Argonauts is a book where every phrase is packed with meaning, and every paragraph is expertly constructed. I would call it a distilled, perfect work, and I want you all to read it now and then immediately respond to this email telling me about it.

FEBRUARY

Alex’s Pick —

Zong! (M. NourbeSe Philip) is centrally concerned with the impossibility of a Black archive. The book-length poem covers the little-reported 1781 Zong Massacre, where the crew of the slave ship Zong murdered over 130 enslaved Black people on board in order to claim indemnity from their insurers. Only one public document exists as a “primary source” in this story: the trial report of the ensuing insurance case, Gregson vs. Gilbert.

Zong! is composed exclusively from words found in this case report, transmuting the corrupted vantage of the state and slavers and the disturbing language of property, profits, and insurance into an “anti-narrative” that challenges the archive available to us. The poem recreates a richer remembrance of the lives of those kidnapped and murdered on the Zong while grappling with the collision of historical record, law, and intergenerational imagination. Philip appropriates and manipulates the public, legal record until she has both uncovered the silence of the Middle Passage in the “official” historical record and created a new archive herself.

MARCH

Alex’s Pick —

R. Zamora Linmark’s Rolling the R’s (1995) is an anti- coming-of-age, anti- coming-out story about the lives of queer Filipino, Vietnamese, Okinawan, and haole fifth-graders growing up in a poor area of 1970s Oahu. Saturated in disco-era pop culture, the characters navigate the simultaneous joys and traumas of living outside the disciplinary regimes of heteronormativity, imperialism, and racial capitalism. The experimental, polyvocal narrative includes Donna Summer lyrics, teen confessions of queer desire, and homework assignments where pidgin becomes a form of resistance. In Rolling the R’s, R. Zamora Linmark artfully illustrates how community can be found in words, performance, and fantasy.

APRIL

Emma’s Pick —

Set against the backdrop of Florida’s Gulf Coast, All Day is a Long Time—a debut novel by author David Sanchez—captures the turbulence of addiction and its aftermath. What begins as an adolescent pursuit of romance and rebellion quickly devolves into a decade-long struggle to regain sobriety. Written with searing vulnerability, All Day is a Long Time sweeps its readers inside the bright and complex mind of a young man grappling with mental illness, homelessness, incarceration, and sobriety.

MAY

Greta’s Pick —

Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family (Sophie Lewis) is a very interesting book of feminist theory that explores how commercial surrogacy disrupts the United States’ model of the nuclear family. Sophie Lewis treats gestational labor as labor, drawing compelling comparisons between surrogacy, sex work, and other gendered, underpaid, and underprotected forms of labor. She uses surrogacy as both a concrete example and as a metaphor for newer, more fruitful forms of relating to one another that are rooted in care and community rather than patriarchy. I found it very accessible and also challenging, which is the ideal combo, in my mind, for any book of theory!

(Image by Epilogue Book Cafe)

JUNE

Niko’s Pick —

Verse and comics, an intersection that proves that poetry is as much a visual medium as it is an oral one. The poems and the graphic interpretations of Embodied: An Intersectional Feminist Comics Poetry Anthology (edited by Wendy Chin-Tanner and Tyler Chin-Tanner) come from a marvelous roster of cis women, trans, and non-binary creators who explore the relationship between gender, identity, and the body. It is a showcase of love, trauma, and empowerment that uses the elegance of prose to address brutal subjects and complex emotions—yet still lays hope and healing for the future. Best of all, there’s a study guide at the end that provokes discussion and introspection around each work. It’s inclusive, and more than that, it’s necessary.

(Image: @spoonbillbooks)

JULY

Alex’s Pick —

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (1982) is an avant-garde exploration of the power that language holds to inflict colonial violence, conceal political histories, and shape collective memory. The book, which is part memoir, shares Cha's relationship to the history of Korea, dealing with concepts of matrilineal remembrance, un/belonging, and speech. She employs images, narrative interruptions and fragments, political maps, anatomical diagrams, and multilingual storytelling to both uncover and undermine colonialism. In doing so, Dictee enacts a resistance to the very violence it interrogates.

AUGUST

Christine’s Pick —

With a life and career spanning the 16th and 17th centuries, Shakespeare’s prolific literary and playwriting remains alive today in the fabric of our culture. Maggie O’Farrell’s novel Hamnet is an exquisite fictionalized account of the life and death of Shakespeare’s young son, from the perspective of Shakespeare’s wife Anne (or Agnes, in the book). In a nuanced flip on focus and power, Shakespeare remains nameless throughout — referred to only as “the husband.” O’Farrell examines the English society dynamics of the time: the intersection of class and gender; the politics of marriage; the rural/urban divide; nature versus industrialization. Above all, Hamnet is a book about our shared humanity of loss and the grief experience.

SEPTEMBER

Greta’s Pick —

Vigdis Hjorth’s Will and Testament is a short, beautifully-written Scandinavian book recommended to me by my grandmother after she took a Scandinavian Feminisms literature class at the University of Washington. The book follows Bergljot, a single woman estranged from her family, after she learns that her family’s cabins––and her father’s will––will be distributed unequally between her and her siblings, pulling her back into the dramas of a family she had rejected long ago. The book explores themes of insanity, hysteria, and familial trauma. It challenges the reader to extend faith in inscrutable characters, even as their stories are warped, or misremembered, or unclear.

OCTOBER

Alex’s Pick —

Kate Brown’s Manual for Survival traces untold stories of the Chernobyl disaster, centering an environmental, intergenerational lens. In this nonfiction work, author Kate Brown uses hindsight, archival research, and first-person recounts to create an alternative manual for survival to the ones handed out by the USSR at the time of the disaster. The deep dive reveals the interconnectedness of the environment, war and militarism, nation-state building, and the politics of disposable populations as they overlap and inform one another in the Chernobyl context. Thirty-six years after the disaster, Manual for Survival functions as both an autopsy of the monumental event which continues to affect lives, communities, and ecosystems and a warning for future disasters, especially the impending climate collapse.

NOVEMBER

Japera’s Pick —

I was recently given Gabrielle Blair’s Ejaculate Responsibly after having experienced an unsuccessful IUD insertion that left me feeling frustrated and even embarrassed. The book, I believe, is a genuine feminist literature that acknowledges and puts the responsibility of unwanted pregnancy and birth control on the one who actually does the impregnation rather than the one who is being impregnated. This read was extremely validating for navigating specifically my own beliefs and values around having “safe sex” and how I want it to look for me despite patriarchal expectations and norms of sex, while also knowing and learning my own boundaries with my body and the birth control industry.

DECEMBER

Greta’s Pick —

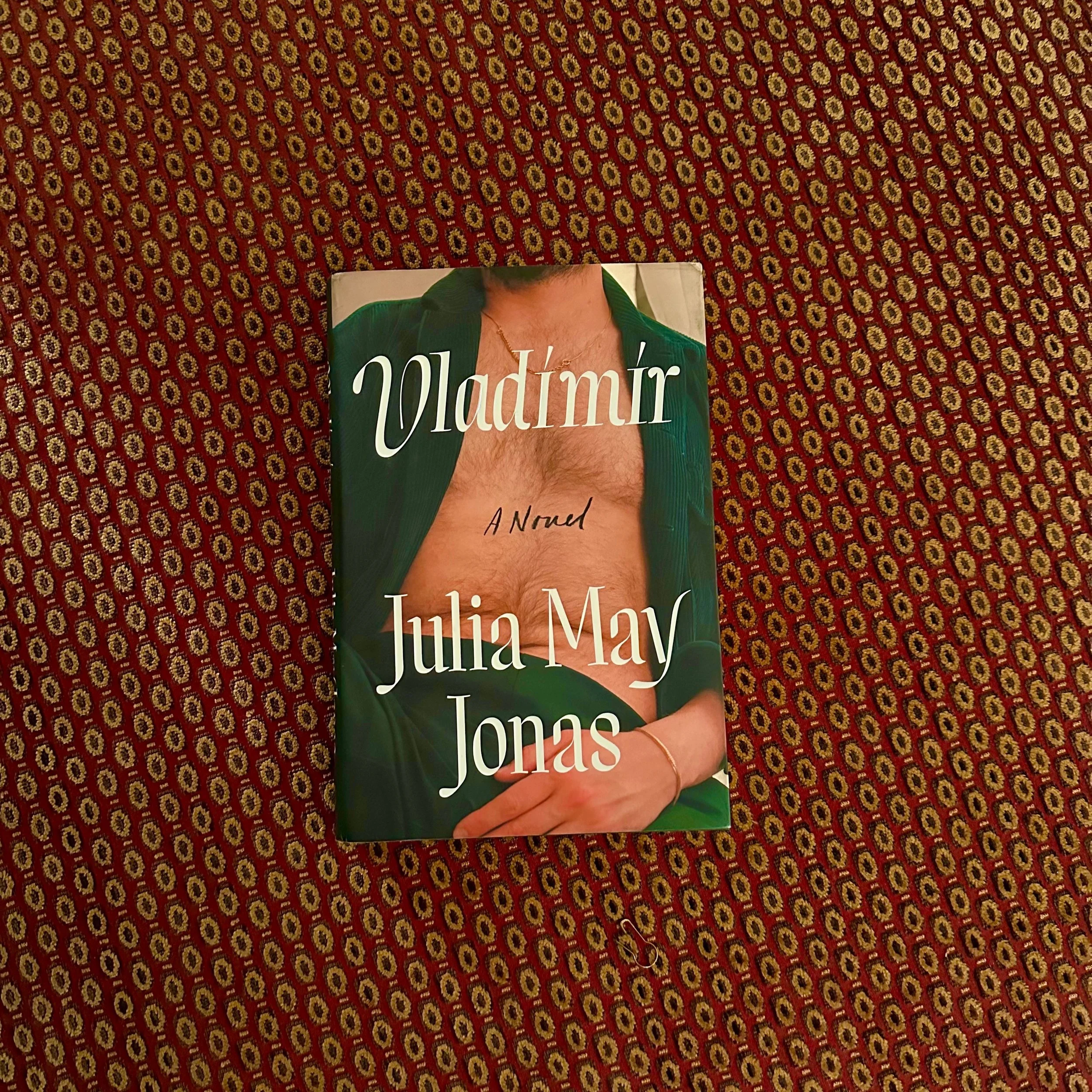

Vladímír, the debut novel by playwright and professor Julia May Jonas, is told from the perspective of a college professor whose husband, a professor at the same college, is in the midst of a scandal. Former students of her husband have recently come forward about relationships with him while they had been at the school, and the student body is enraged. Concurrently, a new, young, hot professor has come to town: Vladimir, in whom the main character is immediately interested.

Vladímír explores power in a nuanced, engaging manner that challenges and critically engages with our cultural conversations about justice and autonomy today. I found it all the more interesting because its portrayals of and concerns with abuses of power––or supposed abuses of power––were imperfect, displaying a genuinely critical relationship with its subject. Already, I have had very interesting conversations with Book Club member Allie about Vladímír; now it’s your turn to please read and write back about what you thought.