Racial Rhetoric in the Pro-Life Movement

It’s Saturday and I’m part of a crowd of white women and a few white men. We’re wearing luminescent green vests with bold black writing on the back that reads ‘CLINIC ESCORT.’ In front of us, women (mostly women of color) arrive in a steady stream to the reproductive health clinic. Not all are here for abortions but quite a few are, given that most pregnancy termination appointments are scheduled at the weekend. Behind us, men and women (mostly of color) preach and mutter and shout, telling the women not to murder their babies, telling them to request a sonogram, telling them that 90% of women who have abortions regret it. And telling them that abortion can be compared to slavery.

This is what clinic escorting in NYC looks like for me. I suspect it isn’t like this in all areas of the country (or even the city). But, let’s face it, these racial dynamics are uncomfortable: college-educated white women in a working class neighborhood standing (quite literally) between people of color. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be out there, providing an alternative viewpoint and some level of comfort to women, their families and their children who are routinely harassed. But it is also vitally important to question why these racial divides exist, to understand the complicated racial history of reproductive rights movements, and to ask: how can we be better?

There is a prevailing idea in the USA that abortion is a ‘white issue’, and a general assumption that Black people are overwhelmingly ‘pro-choice.’ But these ideas overlook the significant influence of Black conservatism and Black opposition to abortion which, far from being anomalous, is deeply rooted in the USA’s racialized and racist political history.

Mistrust of medical, social and legal establishments from minority groups stems from a long history of abuses, such as forced sterilization and the targeting policing of Black populations. These abuses have been medical, political, and personal. Reactions to incidences of medical mistreatment are only exacerbated by contemporary abuses.

The ‘crack baby’ hysteria of the 1980s and 1990s criminalized women with drug addictions, and targeted Black women for perinatal drug use, despite no evidence that they were (or are) disproportionately inclined to engage in it. All of this has resulted in a historically widespread distrust of the government in Black communities. But, in fact, associations between racism and abortion go far deeper, into the heart of historical reproductive rights advocacy.

Margaret Sanger, Founder of Planned Parenthood

In 1921, Margaret Sanger founded the American Birth Control League which in 1942 became Planned Parenthood. For Sanger, the benefit of birth control was not necessarily individual choice and freedom, but to control family size within poorer communities, in an attempt to stem the cycle of poverty. While she worked with a number of Black community leaders in Harlem who held similar beliefs about population control, she also relied on financial support from the wealthy eugenics movement.

At the time, white elites believed that eugenics would encourage the reproduction of stronger, more socially desirable individuals, while stifling the number of children born into ‘undesirable groups.’ It is unlikely that Sanger herself explicitly intended to limit the number of Black children born. However, she did advocate reducing the fertility rate of disadvantaged women and, in a society with a clear racial hierarchy, this effectively meant reducing the number of Black pregnancies.

This was, of course, met with concern by many in the Black community, as it seemed to confirm pre-established concerns of racial genocide. Indeed, throughout the 1960s, reproductive rights movements often allied with population control organizations and, throughout the mid-20th century, government-sponsored family planning programs coerced significant numbers of Black women into being sterilized.

While coerced sterilizations reached their peak in the 1970s, attempts to reduce the Black fertility rate did not stop there. In the 1990s, controversy surrounded the contraceptive implant, Norplant, when lawmakers, legislators, and journalists advocated for the new method of birth control as a way of reducing pregnancy rates amongst poor, specifically Black, people.

At the time, journalist Donald Kimmelman stated “the main reason more black children are living in poverty is that people having the most children are the ones least capable of supporting them.” He suggested that, although no woman should be coerced into receiving Norplant, there should be financial incentives to encourage its use. And this wasn’t far from the truth. Norplant was made available through Medicaid and its provision was included in budgets that were otherwise slashing social welfare schemes, suggesting that targeting Black communities was prioritized over actually reducing inequality.

Considering these repeated legal and medical abuses, it is not surprising that framing abortion as a racial issue has become an effective tactic for pro-life movements. It is both indicative of the benefits of gaining racial authority within politics, and demonstrative of how just how powerful the fear of racial violence is in the USA.

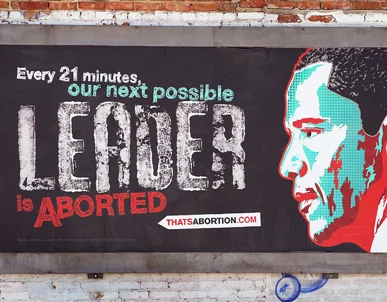

So what does this racial framing look like? Let’s look at a few examples. In 2010, 80 billboards appeared across Atlanta featuring a an African American boy alongside the words “Black children are an endangered species.” This was followed by similar billboards stating “Black Children are in Danger.” The next year, another advertisement showed a picture of an African American girl with the caption “The most dangerous place for an African American is in the womb,” while another featured an image of Barack Obama and stated “Every 21 minutes our next possible leader is aborted.”

Perhaps even more divisively, in the short Frontline film Anti-Abortion Crusaders: Inside the African American Abortion Battle, one pastor tells his youth group “the Ku Klux Klan, still active today, is not our problem; Planned Parenthood has taken it far further beyond what the Ku Klux Klan thought they could possibly take it.”

Some campaigns even emphasize perceived similarities between abortion and slavery. Both Jesse Jackson and Ronald Reagan used the racial trope of ‘people as property’ to compare the foetus and the slave. And one organization’s pro-life campaign drew on a popular turn of phrase within the pro-choice movement, attempting to reduce it ad absurdum. It said, “Once upon a time, we were all just a clump of cells that were bought, traded and sold as property.”

Furthermore, other campaigns have relied on America’s legal history to forward a pro-life argument. One organization asserted that abortion is unconstitutional as denying the rights of the foetus and subjecting its life to the will of its mother is a violation of its 13th Amendment rights.

Similarly, some draw on the infamous Scott v Sandford Supreme Court decision, which denied legal recourse to African Americans under the precept that they could not be considered American citizens. Here, Roe v Wade is presented as the “Dred Scott of our time,” an unconscionable denial of personhood to a human being.

In fact, the protestors at the abortion clinic at which I escort have a large board proclaiming this. And it has not necessarily been a fringe perspective; even Ronald Reagan invoked Scott v Sandford, stating “[Roe] is not the first time our country has been divided by a Supreme Court decision that denied the value of certain human lives.”

Of course, this imagery is powerful. Much like calling someone a ‘Nazi,’ bringing racism into a debate suggests a level of moral certainty and “suspend[s] the usual rules of discursive engagement.” Essentially, to argue that being pro-choice is the modern equivalent of being pro-slavery, is to make the issue of abortion seem morally unquestionable.

This tactic seems to have been somewhat effective. In the 1970s, a survey found that large percentages of individuals living in Black-majority communities agreed that birth control programs were conspiracies to diminish the Black population. More recently, Bird and Bogart conducted research with a small national sample of African Americans. While this study was not explicitly focussed on pregnancy termination, it reveals attitudes that might well inform views on abortion.

For example, 49% agreed that “Whites want to keep the numbers of African American people down” and 21% somewhat or strongly agreed that “The government is trying to limit the African American population by encouraging the use of condoms.” While it should be noted, however, that only 6% endorsed the idea that “Birth control is a form of Black genocide,” this data does suggest that significant numbers of Black people in the United States remain suspicious of reproductive healthcare.

This could well have an impact on the number of people who have access to, and use, abortion services. For example, it has been noted that this rhetoric may be especially detrimental to Black women, who exist at the intersection of racial and gender issues. Here, the use of racialized language may become a way for Black men (who head the Black pro-life movements) to control Black women. Those women who do speak out in support of accessible, legal abortions may be labelled ‘dupes’ to White supremacy or traitors to their race. So, given the USA’s chequered medical history, what should be done?

First and foremost, we need to look at the responses coming from the Black community as a whole, African American women in particular, and PoC reproductive justice movements. Black women have been providing or openly advocating for birth control and access to abortions for centuries. In the late nineteenth century, Vaseline or quinine was placed over the mouth of the uterus to help prevent conception. Later, in the 1920s and 1930s, Black media continued to be a source of birth control information and Black leaders emphasized the importance of family planning to the health of the community.

More recently, there has been a shift towards intersectional activism. This movement has been named “reproductive justice,” and it attempts to tackle a range of issues that have been previously ignored by mainstream reproductive rights groups. The SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Collection was founded in 1997 by marginalized women activists who felt that the pro-choice movement was not considering the unique challenges faced by working class and marginalized women.

They focused on contextualizing the complexities of reproductive health as they exist for uterus-owning people of various demographics and marginalized social groups. Importantly, this includes the freedom both to prevent or terminate pregnancy, and to reproduce without unnecessary state intervention (such as forced sterilizations or targeted policing) and bring up their children in safe, economically stable environments.

Furthermore, they condemned the racialized pro-life billboards, which stated “Black children are an endangered species,” saying “the mere association between the born and unborn with endangered animals provides a disempowering and dehumanizing message to the black community, which is completely unacceptable.”

Fundamentally, women-of-color grassroots reproductive justice organizations tend to reject the pro-life/pro-choice paradigm, arguing that it serves the White majority and does not account for the experiences of women of non-dominant identities. Accordingly, neither side effectively addresses the economic, political and social conditions that inform reproductive choices.

In the end, racialized pro-life rhetoric may have problematic implications for Black women, the larger Black community, and reproductive rights as a whole. Doctors at family planning clinics may be the only medical professionals that individuals (especially teenagers) in disadvantaged communities have access to or visit, so it is important that Black people are not shamed into avoiding these services.

Nevertheless, it is also vital that activists (and White activists in particular) take concerns regarding “Black genocide,” and parallels drawn between abortion and slavery seriously and acknowledge the legal and medical abuses that have caused distrust in the African American community. As pro-choice activists, we must demonstrate an understanding of the material conditions, and social, political and economic factors that influence reproductive choices in a range of communities.

Ultimately, the White, middle-class activist base should understand that emphasizing ‘individual choices’ does not account for the full range of reproductive issues facing people capable of pregnancy in the USA. As scholar Andrea Smith says “a reproductive justice agenda must make the dismantling of capitalism, white supremacy, and colonialism central to its agenda.” Ensuring anyone may end a pregnancy without interference is a vital step. However, only once all people can raise children without the interference of social and economic inequalities will they truly have the freedom to choose.