Heroes: Ana Mendieta

content warning: mention of intimate partner violence, blood, suicide

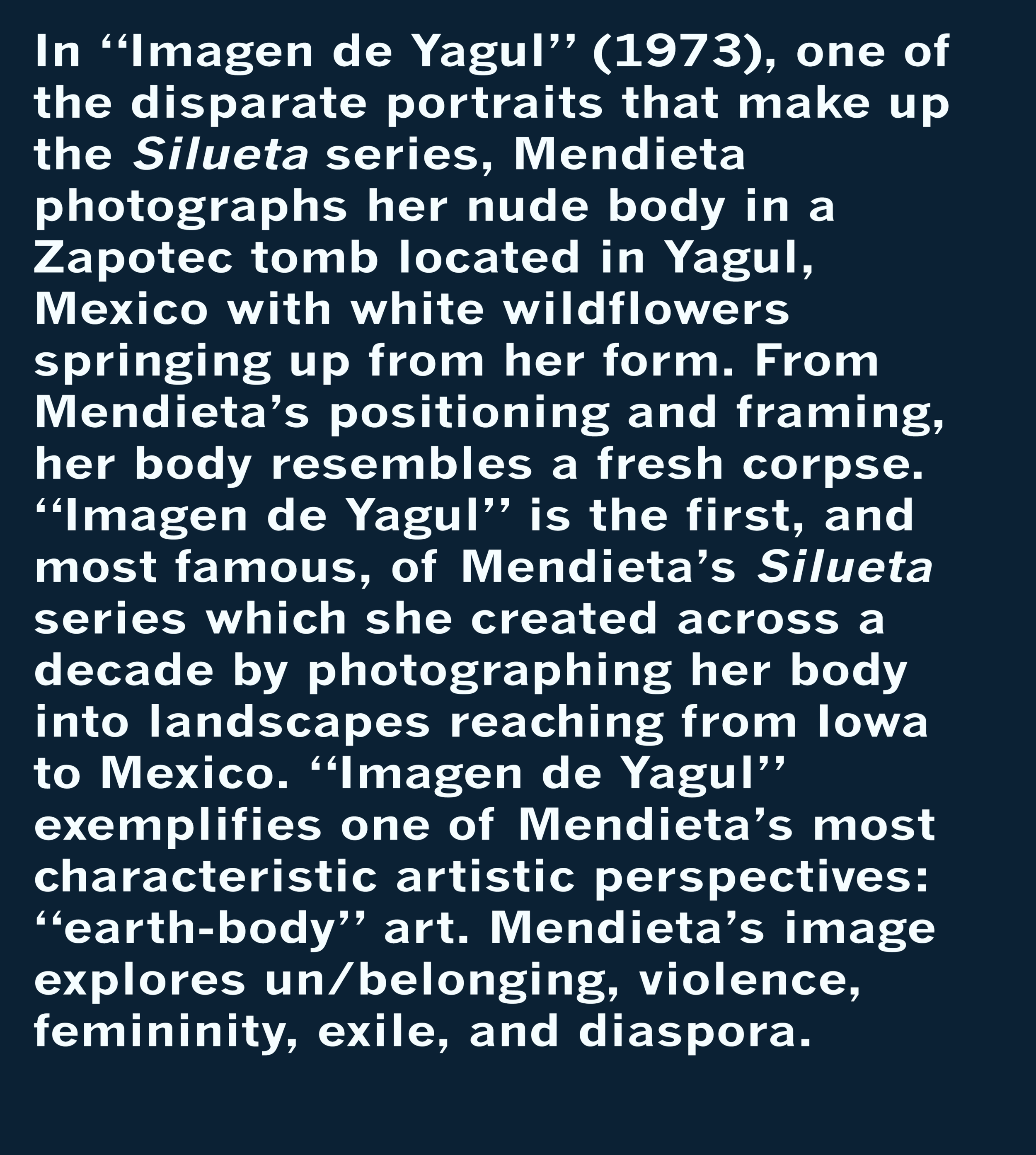

I was immediately gripped by Ana Mendieta’s art when I saw it for the first time at the “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985” exhibit at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Specifically, her 1972 Facial Hair Transplants photo series stuck out amongst an array of other feminist works at the exhibit, exemplifying Mendieta’s interest in gender and form. Mendieta used her body, her gender, and her femininity as the primary subject matter of her work. In doing so, Mendieta leveraged provocative, transnational critiques of patriarchy, gendered violence, and the gender binary through her camera lens.

Ana Mendieta was born in Havana, Cuba in 1948. One year after the Cuban revolution, when Mendieta was only 12 years old, she and her sister were sent to the United States where they would grow up as adopted refugees, part of the Peter Pan Operation. Mendieta and her sister spent most of their adolescence across foster homes in Iowa, which were starkly different from the home of their Cuban childhood. Knowing little English upon first arrival to Iowa, both Mendieta and her sister relied upon each other, and their interest in creative expression, for company. Alienation -- both in the form of family separation and cultural difference -- greatly influenced Mendieta’s burgeoning artistic interests and later informed her unique creative perspective.

Alison Jacques Gallery

Most of Mendieta’s work strikes the viewer as surreal, magical, jarring, out of place. Mendieta creates new worlds in her images rather than attempting to approximate or reflect worlds that already exist. This is an especially unique way in which Mendieta’s diasporic sensibilities appear in her work: as an artist who didn’t completely identify with the country she left nor the one to which she moved, Mendieta instead created new places and body-land relationships. In her work, she notably imagines herself returning––not to Cuba, but to the womb.

SF MOMA

Mendieta is considered a performance photographer and has created films, sculpture, drawings, performance installations, and photo series. Mendieta’s body of work is part of the Land art and Body art movements, or what she referred to alternatively as “earth-body” art. Mendieta often appears in her own work, the influences of which are primarily credited to Afro-Cuban religious traditions (such as Santería*) and critique of gendered violence.

The purpose of many of Mendieta’s series and performance was to provoke discomfort, rage, and distress in the face of violence against women. By using her own body and even blood as proxy, Mendieta called daring attention to gendered violence, namely in the Sweating Blood film (1973), the Self-Portrait with Blood series (1973), and the Body Tracks series (1982). Mendieta is believed to have created each of these pieces in response to an on-campus rape and murder of a fellow University of Iowa student, Sarah Ann Ottens, in 1973. Ultimately, Mendieta herself died an early death as a result of intimate partner violence.

The Missive

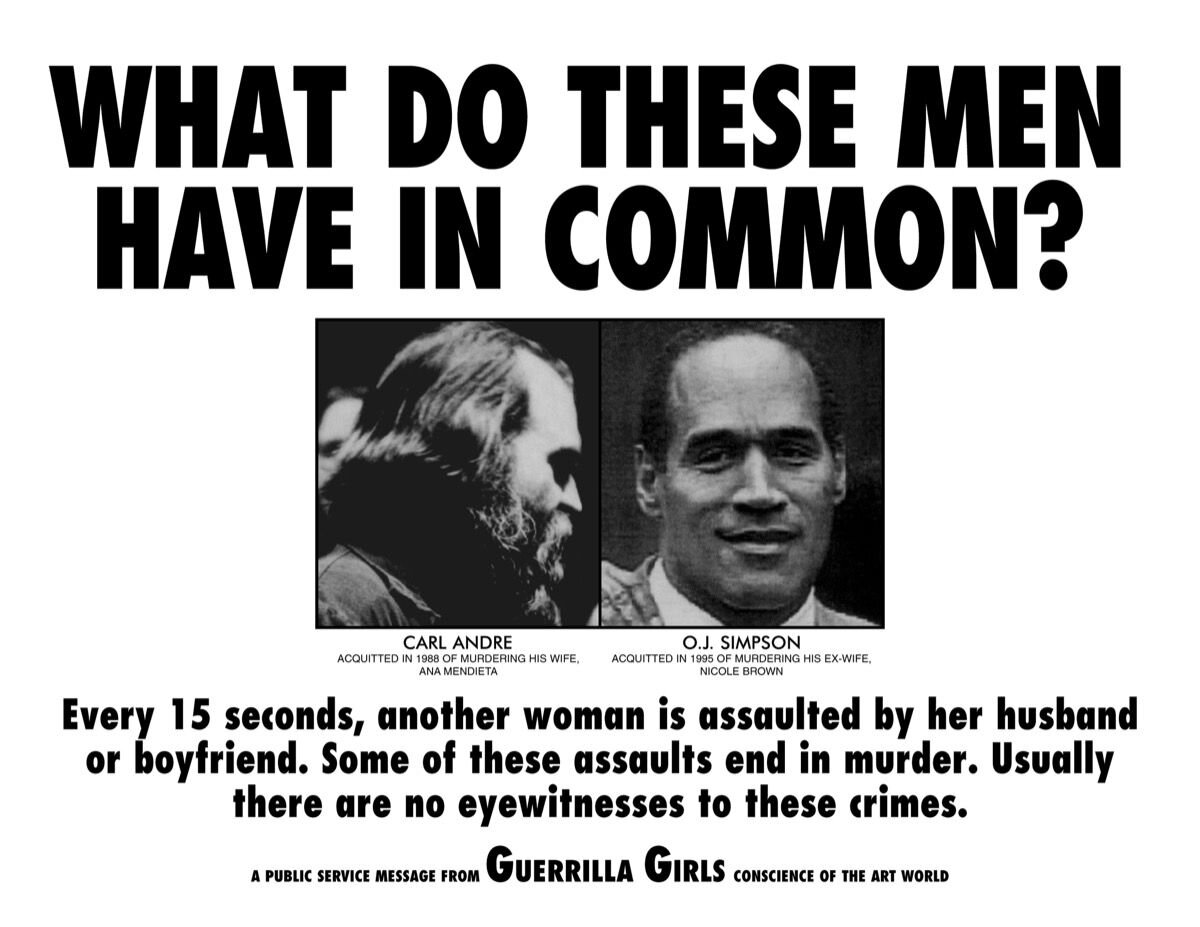

In 1985, Mendieta was found dead at the bottom of her apartment building after falling 33 stories. Mendieta had been home with her boyfriend Carl Andre when neighbors distinctly heard arguing and then Mendieta screaming, “no.” Andre was later discovered with scratch marks on his face. Despite the overwhelming evidence that Andre pushed Mendieta, he maintained that she was depressed over the fact that he was becoming a more successful artist than she was, and that her depression drove her to suicide. Andre was ultimately found not guilty in court, yet Mendieta’s close friends have never stopped insisting that Mendieta would not have taken her own life. Due to Mendieta’s profound advocacy against gendered violence, her death became a rallying point for feminists in the U.S. and beyond. Mendieta never got the justice she deserved, but her art and her memory live on, mobilizing feminists to this day against gendered violence.

Guerrilla Girls, Artsy.net.

Remembering Ana Mendieta’s life and poring over her art are important ways that feminists can honor her legacy and continue her feminist work. Undoubtedly, Mendieta’s daring aesthetics have influenced artists after her, as they have also impacted Uterish’s own engagement with femininity and the natural world. Mendieta’s lasting impression is of a daring creative who asked feminist questions about belonging (in gender, in body, in culture, and in borders) and violence through her art.

———

*Santería is an Afro-Cuban religious tradition that stems from survival practices of enslaved Africans that were forcibly brought from the Western coast of the African continent to Caribbean islands in the 16th Century. In the colonial, slave-holding Carribean, Catholicism was imposed on enslaved Africans. Santería emerged as a result of enslaved Africans hiding Yoruban and other West African traditions inside of the architecture of Catholicism, including language, idols, and practices. Santería is still practiced today in the Carribean and has a focus on deity, sacrifice, and ritual.